Transition economies

Transition economies

A transition economy is one that is changing from central planning to free markets. Since the collapse of communism in the late 1980s, countries of the former Soviet Union, and its satellite states, including Poland, Hungary, and Bulgaria, sought to embrace market capitalism and abandon central planning. However, most of these transition economies have faced severe short-term difficulties, and longer-term constraints on development.

The problems of transition economies include:

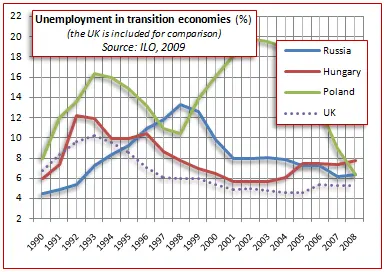

Rising unemployment

Many transition economies experienced rising unemployment as newly privatised firms tried to become more efficient. Under communism, state owned industries tended to employ more people than was strictly needed, and as private entrepreneurs entered the market, labour costs were cut back in an attempt to improve efficiency. As the newly established private firms became subject to greater competition some were driven out of the market, which created job losses. In addition, a reduction in the size of the state bureaucracy also meant that many employees of the state also lost their jobs.

Between 1990 and 1997, unemployment rose in the three selected transition economies and was consistently above more well-established, market-based economies like the UK. Of course, the global recession of 1990 – 92 accounts for some of the rising unemployment over that period. Market reforms adopted in these countries have gradually brought down unemployment in the transition economies, to be on a par with many established market economies.

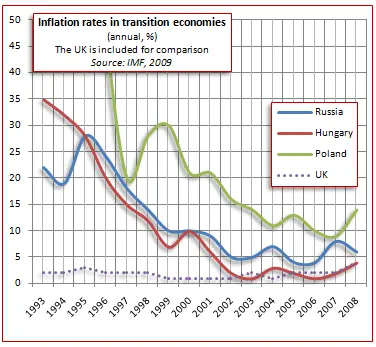

Rising inflation

Many transition economies also experienced price inflation as a result of the removal of price controls imposed by governments. When this happened, the newly privatised firms began to charge prices that reflected the true costs of production. In addition, some entrepreneurs exploited their position and raised prices in an attempt to profit from the situation.

Annual inflation in the transition economies between 1990 and 1997 averaged around 20%, but then fell, moving much closer to the average found in the market economies of Western Europe.

Lack of entrepreneurship and skills

Many transition economies suffered from a lack of entrepreneurs and entrepreneurship, which make it more difficult to reform their economies and promote market capitalism. In addition, there was also a skills gap with few workers having the necessary skills required by employers in the newly privatised firms.

Corruption

It is alleged that corruption was widespread during the early years of transition in many former communist countries, and this inhibited the effective introduction of market reforms. Many products were poorly made and sold in unregulated and illegal markets, and many have claimed that criminal gangs and widespread racketeering filled the vacuum left by the deposed communist regimes.

Lack of infrastructure

The transition economies also suffered from a lack of real capital, such as new technology, which is required to produce efficiently. This was partly because of the limited development of financial markets, and because there was little inward investment from foreign investors. Clearly, this has changed as the transition economies have reformed, and joined the global market, which has encouraged inward investment (Foreign Direct Investment – FDI) from around the world.

Lack of a sophisticated legal system

Under communism, the state owned all the key productive assets, and there was little incentive to develop a sophisticated legal system that protected the rights of consumers, and regulated the activities of producers. Market-driven economies will only develop when citizens are granted extensive property rights, and can protect these rights through the legal process. This was large absent in the former communist transition economies.

Moral hazard

The problem of moral hazard implies that inferior performance can arise when the risks associated with poor performance are insured against. For example, if individuals insure the contents of their house against theft, they are more likely to leave their windows open. In the context of transition economies, under communism people felt that the state would insure them against the risks associated with global competition, including the risk of losing their jobs. The consequence is that many workers remained inefficient and unproductive, knowing that employment prospects would not be reduced.

Inequality

Economic transition also led to rapidly increasing inequality as some exploited their position as entrepreneurs and traders in commodities, while others suffered from unemployment and rising inflation.