Linear growth theories

Linear growth theories

Rostow

One of the first growth theories was that proposed by American economic historian Walt Rostow in the early 1960s. As a vigorous advocate of free market capitalism, Rostow argued that economies must go through a number of developmental stages towards greater economic growth. He argued that these stages followed a logical sequence; each stage could only be reached through the completion of the previous stage.

Stages

- Traditional society, dominated by agriculture and barter exchange, and where science and technology are not understood or exploited.

- Pre-take-off stage, with the development of education and an understating of science, the application of science to technology and transport, and the emergence of entrepreneurs and a simple banking system, and hence rising savings.

- Take-off, with positive growth rates in particular sectors and where organised systems of production and reward replace traditional methods and norms.

- The drive to maturity, with an ongoing movement towards a diverse economy, with growth in many sectors.

- The stage of mass consumption, where citizens enjoy high and rising consumption per head, and where rewards are spread more evenly.

Rostow’s work, like many other accounts of growth, points to the significance of the accumulation of savings to achieve take-off – in this case as a necessary condition for the movement from traditional to developed societies.

Harrod and Domar

The importance of savings and investment is also central to the work of Harrod and Domar. According to this theory, and those derived from Harrod and Domar’s work, there are two determinants of the rate of growth of a country. The first looks at the relationship between changes in the capital stock of a country, that is its capital investment, and its output, called the capital-output ratio. This shows how much new capital, such as £10, is needed to create a given amount of new national income, such as £2.

The second element of the model considers the relationship between savings and national income is called the savings ratio, and this shows how much is saved, such as £10, from a given amount of national income, such as £100. The model indicates how these two ratios affect the rate of growth. Essentially, the higher the savings ratio, the more an economy will grow; and the higher the capital-output ratio, the higher the rate of growth.

For Harrod and Domar, economies must save and invest a certain proportion of their income to grow at a certain rate – failure to develop is caused by the failure to save, and accumulate capital. For take-off to happen, savings must be accumulated.

Savings and investment

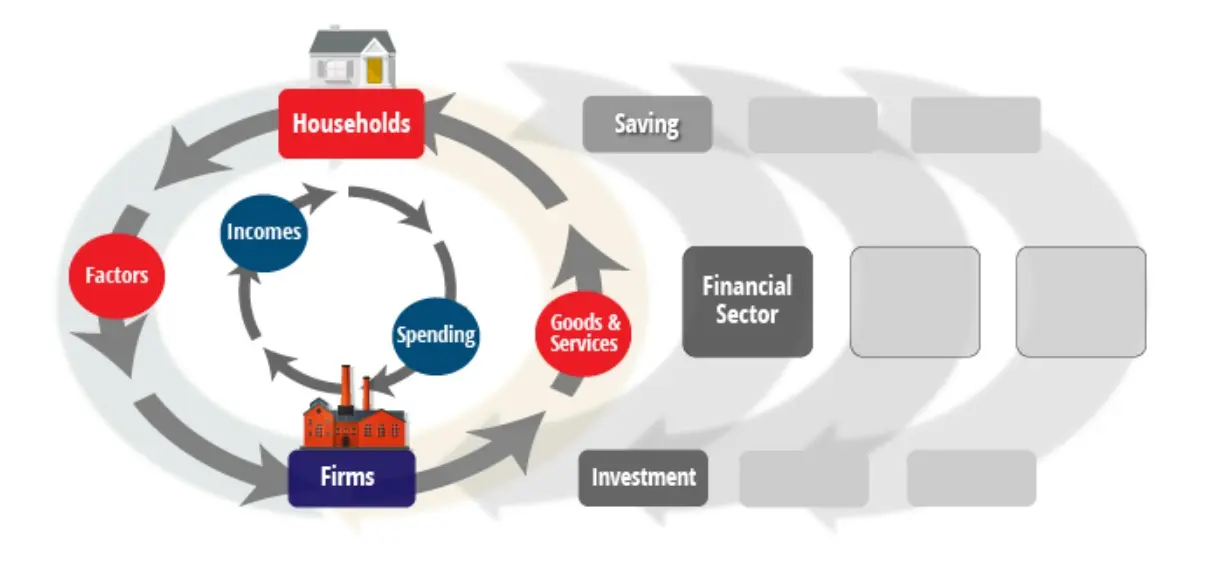

The simple circular flow model indicates the connection between savings which provides a flow of funds, and for investment, which requires abstinence from consumption in order that resources can be freed up for investment.

Investment itself is an injection back into the circular flow, and increases the economy’s capacity to produce more output in the future.

Savings and capital-output ratios

The savings ratio indicates the ratio of savings to national income. The capital-output ratio indicates how much capital is needed to generate a given amount of national output.

Evaluation of linear stage theory

The theories of Rostow, Harrod and Domar, and others consider savings to be a sufficient condition for growth and development. In other words, if an economy saves, it will grow, and if it grows, it must develop. Aggregate savings are largely determined by national income, so if income is low, savings will not be accumulated. According to Rostow’s theory, saving between 15% and 20% of income (a savings ratio of 0.15 – 0.2) would be enough to provide the basis for growth. If this level of saving is maintained, growth would also be sustained.

Major criticisms of this approach include:

- Although saving is regarded as highly significant, modern growth theory takes into account a broad set of growth factors.

- Other criticisms of stage theory point to general weakness in terms of the unrealistic assumptions of these models, such as perfect knowledge, stable exchange rates, and constant terms of trade.

- Most analysis was based on the reconstruction of Europe after World War II, but most developing countries do not have Europe’s institutions, attitudes, financial markets, levels of education, and desire to succeed as found in Europe.

- Modern theory tends to see savings as a necessary but not sufficient condition for growth.