Promoting development

Policies to promote development

In trying to develop, countries can either look inwards or outwards.

Inward and outward looking policies

Inward looking

Inward looking strategies were typical of the general approach to development which dominated thinking after the Second World War. This approach is interventionist and protectionist, and guided policy making in many African and Latin American countries, and in some countries still does.

The general economic strategy was referred to as import substitution, which meant encouraging the development of domestic industry ‘under cover’ of protective barriers, such as tariffs and quota. The industries targeted were those that provided the largest quantity of imports. Therefore, in the case of Japan, import substitution meant developing strong motor vehicle and consumer electronics industries. Inward looking strategies also involved the heavy subsidisation of domestic producers as well as limiting the activities of multi-nationals.

The benefits of inward looking policies

Inward looking policies did generate some short term benefits, such as the protection of infant and declining industries; job creation; increased income and preserving traditional ways of life. However, the consensus is that the challenges of globalisation require a more outward looking approach.

Tourism?

Video courtesy of World Trade Organization; Rue de Lausanne 154; 1211 Geneva 21; Switzerland: Link: WTO Video.

Tourism in Africa

An outward looking strategy, such as promoting tourism, is seen as a more modern approach to development, and one that relies less on government intervention. A number of important global events forced many developing countries to become outward looking, including a rising development gap between countries adopting inward and outward looking policies. In addition, the collapse of communism created an opportunity to adopt more outward looking policies. Those that have adopted them, including India and China, clearly benefitted from increasingly outward looking policies in terms of growth rates and reduced poverty.

The benefits of outward looking policies

The benefits of outward looking policies are derived from the benefits of free trade. For example, free trade brings welfare gains from tariff removal and increased competition and efficiency. In addition, outward looking countries may be better able to cope with globalisation and with external shocks. However, the financial crisis and its after-effects have forced many national governments to re-think their policies and to minimise the risks of an outward looking approach.

Developing particular sectors

One strategy for a country looking to develop is to try to develop one of its sectors.

It would appear that there is a strong correlation between the level of development of an economy, and the proportion of its national output being generated by different sectors.

Development theory suggests that the greater the significance of agriculture, the less the level of development. Conversely, the more prominent the service sector, the greater the level of development.

Primary markets

Many developing countries specialise in agricultural and other primary products. Indeed, the principle of comparative cost advantage suggests that specialising in commodities and products with the lowest opportunity cost will provide the best opportunity for economic development. However, over-specialisation, particularly in terms of primary production, can be highly risky.

A country may remain under-developed if it specialises in producing a few primary products. There are several reasons for this.

Low value-added un-branded products

Primary products, such as food and commodities, are bought and sold in markets which are virtually perfectly competitive. This means that products are un-branded and homogeneous, with a low valued added, and therefore low-priced. As a result, the sale of such commodities generates a relatively small share of global income, so the rewards to factor inputs will also be limited. This does not create an economic environment in which entrepreneurs can flourish and take risks to accumulate short-term supernormal profits.

Inconsistent yields

Yields from land are likely to be inconsistent because of variations in growing conditions.

Price instability

Price instability, which is an inherent feature of primary markets, can make it extremely hard for producers to survive. It also deters investment in new technology, which requires a stable macro-economic environment.

Susceptibility to global shocks

If countries rely on producing a small range of agricultural products, they are more likely to be adversely affected by global shocks.

Unfavourable elasticity

Primary products have low income and price elasticity, which means that, as world incomes rise, proportionately less income is allocated to primary products, and more is allocated to manufactured goods, and services. In addition, commodity prices often fall in relation to manufactures but, because of the relatively low price elasticity, sales revenue falls when prices fall. In addition, export prices of commodities sold by developing countries tend to fall relative to import prices of manufactures from developed countries, hence the terms of trade of many developing economies fall. This means they have to export increasingly more commodities to pay for the same volume of imported manufactures, including both consumer and capital goods.

Unfavourable terms of trade

A country’s terms of trade indicate how high a country’s export prices are in relation to their import prices, and is expressed as:

| Index of Export prices __________________ |

x 100 |

| Index of import prices |

The Prebisch-Singer hypothesis

The hypothesis states that, over time, the terms of trade for commodities and primary products deteriorates relative to manufactured goods. This hypothesis contributed to the general view that it was dangerous to rely on agriculture to secure growth and development. This means that, just to keep up with developed economies and maintain the existing development gap, countries relying on producing and exporting primary products, whose terms of trade decline, must continually increase output.

The hypothesis also provided the basis for an inward looking approach. This suggests that countries are encouraged to switch to manufacturing, and undertake import substitution. This means encouraging countries to stop importing goods with increasing terms of trade, and develop their own industrial base so that they can produce these goods for themselves.

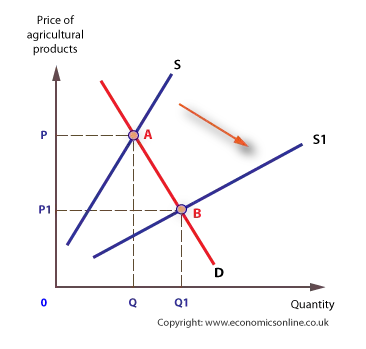

Falling farm incomes

In the long run, the income of many primary producers has fallen because the global supply of food has risen. This is the result of a greater use of new technology and better crop yields, and because of new entrants into the global marketplace, such as the entry of Vietnam into the coffee market.

However, demand has not increased in the long run, so revenue (P x Q) falls. In fact, the demand for some food has fallen over time. Revenue, 0PAQ, is clearly larger than revenue, 0P1BQ1.

Unstable prices

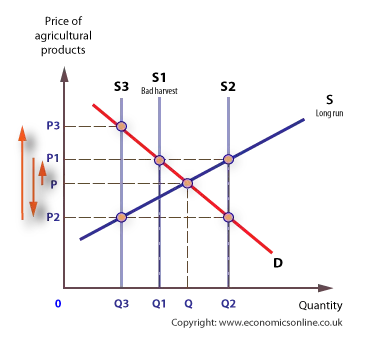

The cobweb diagram best explains the tendency for price instability of agricultural products.

Initially, we can assume a stable equilibrium price, P. There then follows a negative supply shock, such as a crop failure caused by disease or bad weather. The short run supply curve following the shock, (Q1, at S1), is lower that planned (Q). When this smaller quantity is taken to market, its price is driven up to P1. With price at P1 there is an incentive plant a bigger crop in the following year. In the following year, planned output rises to Q2, but this drives price down to P2.

The process continues until the price is so low that producers are driven out of the market.

There is clearly a significant information failure – farmers and growers are not fully aware of the impact of their decisions in one year on the price of products in the following year.

Remedies

Buffer stocks

Buffer stocks are stocks that have not yet been taken to market, and are held to help regulate price from year to year.

Buffer stocks can help stabilise price by taking surplus output and putting it into storage. Alternatively, with a bad harvest, stock is released from storage. A target price can be achieved through intervention buying and selling. Buffer stocks can stabilise farm prices at the target price, and help stabilise farmers’ incomes.

Evaluation of buffer stocks

While buffer stocks can help stabilise price, there are a number of disadvantages, including the following additional costs to society, such as initial building costs, extra storage, insurance, and management.

A further problem is that not all products can easily be stored because they are perishable. Buffer stocks also rely on starting with a good harvest so that the surplus can be put into storage. Without stocks in the system, it is not possible to react to a poor harvest by releasing stock.

Critics also argue that they distort the operation of free markets and prevent the price mechanism working effectively. Finally, there is the potential problem of moral hazard – buffer stocks provide insurance against poor harvests and may encourage producers to be inefficient.

Guaranteed prices

Guaranteeing a price to producers (at P1), is another way of stabilising prices and incomes.

A guaranteed price is a price that a government or authority commits to paying, irespective of the output produced.

However they can also be criticised because:

However, they can also be criticised because they encourage over-production, creating a surplus of Q2 to Q1. In addition, guaranteeing prices can promote inefficiency – why should farmers bother to be efficient if they are guaranteed a buyer? This is another example of moral hazard. There are also extra costs of storage or disposal.

Set-Aside programmes

Set-aside schemes involve farmers and growers being paid to ‘take land out of production’. They are used widely in the EU and USA. Set-aside can be effective because it can prevent surpluses happening in the first place, and hence avoid storage, distribution, and management costs.

Export subsidies

An export subsidy involves farmers and growers being paid a subsidy to export their surpluses at artificially low prices. However, other countries can retaliate, and impose tariffs because it can be argued that this is unfair competition.

Quotas

Producers can be told how much to produce, to avoid over or under production in response to shocks. It can be argued that they are effective, because prevention is better than cure. However, there is a potential Prisoner’s Dilemma, where farmers cheat by over producing because they predict that other farmers will also over produce.

Better information about future shocks

Better use of the internet and computer technology can also be used to provide farmers with information about weather and other potential shocks. However, small producers in developing countries are unlikely to be affected. A government can also provide special education, such as establishing special agricultural colleges, and providing courses to educate and train farmers and growers.

Development of agriculture

Most development theories conclude that improvements in agriculture are crucial to development prospects. Agriculture can be developed by a range of policies, including extending property rights to individuals so that they have an incentive to be more productive. It may also be necessary to promote land reform and improvement programmes.

Commodity Agreements

Commodity agreements are arrangements between producing and consuming countries to stabilise markets and, from the producer’s perspective, raise average prices. These agreements are common in many markets, including coffee, tea, and sugar.

Example – The International Cocoa Agreement

In 2003 an agreement was made between the seven main cocoa exporting countries; Cameroon, Ivory Coast, Gabon, Ghana, Malaysia, Nigeria and Togo, and the main importing countries ; fifteen EU members, plus Russia, the Slovak Republic and Switzerland. The main purpose of the ‘agreement’ was to promote the consumption and production of cocoa on a global basis. The agreement is planned to last until 2010, and, as well as promote cocoa as a product, attempts to stabilise cocoa prices, which have been falling steadily over the past 10 years.

These agreements often involve intervention schemes, such as buffer stocks, and usually only last for a few years, whereupon they have to be re-negotiated. They are different from cartels such as OPEC, largely because they involve both producer and consumer countries.

Many countries have promoted tourism as a means of achieving development, including Cuba. To ease the problem of falling revenues from sugar, and from the dramatic reduction in aid following the collapse of the Soviet Union in the early 1990s, Cuba turned to tourism. This included encouraging the building of hotels by foreign firms and the development of certain holiday resorts, such a Varadero.

The advantages of tourism

Multiplier effects

Given the high marginal propensity to consume (mpc) in developing economies, the injection of tourist revenue can, through a multiplier effect, have wide repercussions on economic activity, including job creation.

Infrastructure

The development of a tourist industry requires the construction of infrastructure, including airports and roads. Once available for use, transport costs can fall, and the efficiency of domestic producers can increase.

Encouraging FDI

A growing tourist industry encourages further inward investment associated with the provision of services.

Currency

Tourism can be a highly effective at generating foreign exchange, especially in comparison with low-value commodities.

Diversification

Tourism can help create a more balanced and diversified economy, with a developing service sector which is often seen as a key indicator of economic progress.

The disadvantages of tourism include the following:

Little revenue is retained

Tourist revenue may go to firms based in other countries, such as travel agents and tour operators. The owners of the hotels may reside abroad, with profits going out of the country.

Dual economy

Tourism may lead to the emergence of an unofficial parallel economy, often with the unofficial part being based on the US$, as in the case of Cuba. Given the nature of these cash economies, very little tourist spending ends up as tax revenue. This means that the governments of many developing countries do not receive sufficient revenue from tourism to spend on infrastructure, education, and healthcare.

Negative externalities

Tourism can generate a number of negative externalities, including the costs of overcrowding; the loss of areas of natural beauty; the exploitation of historic sites; excessive demands on local infrastructure and the diversion of resources from key industries, such as food production.

Instability

Tourist income is potentially a highly unstable source of income. Sudden changes in the level of tourism can occur for a number of reasons, including changes in national incomes in developed economies. Tourism has a high income elasticity of demand meaning that spending is very sensitive to the business cycle.

In addition, tourist travel is susceptible to health, security, and safety scares, such as Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARs), which adversely affected travel to China and Canada during 2004, the ebola outbreaks of 2014 and 2019, terrorist attacks, and natural disasters like the Asian tsunami.

Changes in exchange rates can also make the tourist markets unstable. For example, the fall in sterling between 2007 and 2009 increased the price of foreign holidays, and caused more UK holiday makers to take their holiday at a UK destination. A similar effect occurred as a result of the fall in sterling after the Brexit vote.

Lastly, changes in taxes, such as changes in airport taxes, carbon taxes, and changes in duty-free allowances can all influence demand for tourism.

Structural adjustment policies (SAPS) attempt to encourage developing economies to put greater emphasis on market forces and market reforms. Such policies are closely associated with free-market economics, which became highly influential during the late 1970s and 1980. The theory of structural adjustment profoundly influenced the development of international financial organisations like the World Bank and IMF during the 1980s. Since then, both the IMF and World Bank require structural adjustment as a condition for lending to developing countries.

Features of SAPs

Economic stabilisation

SAPs attempt to stabilise the macro-economic environment to help an economy cope with globalisation and external shocks. Such policies include:

- Tight monetary policy, including raising interest rates, or controlling the quantity of money.

- Fiscal controls, including reducing the level of subsidisation by the state; controlling the size of the public sector; and cutting back on the level of public sector pay.

- Exchange rate depreciation, to give a boost to exports.

Structural policies include:

- Liberalising trade by removing barriers which protect domestic firms, to enable countries to discover their true comparative advantage, and specialise in producing goods and services with the lowest opportunity cost.

- Privatisation of state industries to generate micro-economic efficiency gains, and encourage inward investment as overseas banks, firms and private citizens look to invest in the newly privatised industries. This would create a positive multiplier effect on the domestic economy.

- Measures to increase capital mobility, such as eliminating ‘capital controls’ which stop foreign firms withdrawing capital, and encouraging the development of stock markets.

The Washington Consensus is a phrase used to describe the general preference of the USA administration and many of its political allies, and, critically, the IMF and World Bank, for structural reforms to accompany any loans or aid. The ‘consensus’ can be summarised as the view that countries looking to develop and benefit from loans, grants, aid and political support, should adopt the following policies:

- The widest use possible of market forces to allocate scarce resources, including the privatisation of utilities.

- Free trade and an export orientation.

- Improvements in education and healthcare.

- Sound fiscal policies.

Issues

Structural adjustment policies often involve considerable austerity for people already highly impoverished. In addition, fiscal prudence may mean governments reducing spending on long term projects involving education and healthcare, with a loss of positive externalities associated with health and education.

In addition, privatisation does not necessarily help stabilise an economy and can raise prices and reduce employment. The liberalisation of capital markets can create exchange rate volatility which can destabilise an economy in the short run. The recent credit crunch has clearly highlighted the risks associated with free trade in capital and finance, and from globalisation in general. However, supporters of structural adjustment stress that, in the long-run, growth and development are much more likely to emerge when the principles of structural adjustment are fully applied to developing countries.

Go to: Financing development