Demand shocks

Demand shocks

The equilibrium position of national income will change, ceteris paribus, following an economic shock. Economic shocks either arise from the demand side or the supply side.

Exogenous and endogenous demand side shocks

An exogenous demand side shock is one caused by a sudden change in a variable outside the aggregate demand (AD) model, whereas an endogenous shock comes from within the model. For example, a sudden change in investment is an endogenous shock, because investment, ‘I’, is in the AD equation, whereas a sudden change in the exchange rate is an exogenous shock because exchange rates are not directly included in the AD equation.

A number of demand side shocks can directly affect planned spending in the economy. These include:

- Shocks affecting household or corporate spending, such as changes in unemployment, savings, confidence, wages, and profits.

- Shocks associated with changes in liquidity and the availability of consumer and business credit, as in the recent credit crunch.

- Changes in spending associated with changes in house prices, share and bond prices, called wealth effects.

- Shocks affecting investment spending, including changes in bankruptcies, business confidence, and profit levels.

- Changes in government finances, brought about by wars, and changes in unemployment.

- Shocks directly affecting exports or imports, such as the economic collapse of a trading partner.

- Other demand side shocks affect planned spending indirectly, such as changes in:

Interest rates, which affect both consumer and investment spending.

Tax rates, which also affect consumer and investment spending.

Exchange rates, which affect exports and imports.

Changes in any of the above will shift the position of the AD curve.

Shifts in AD

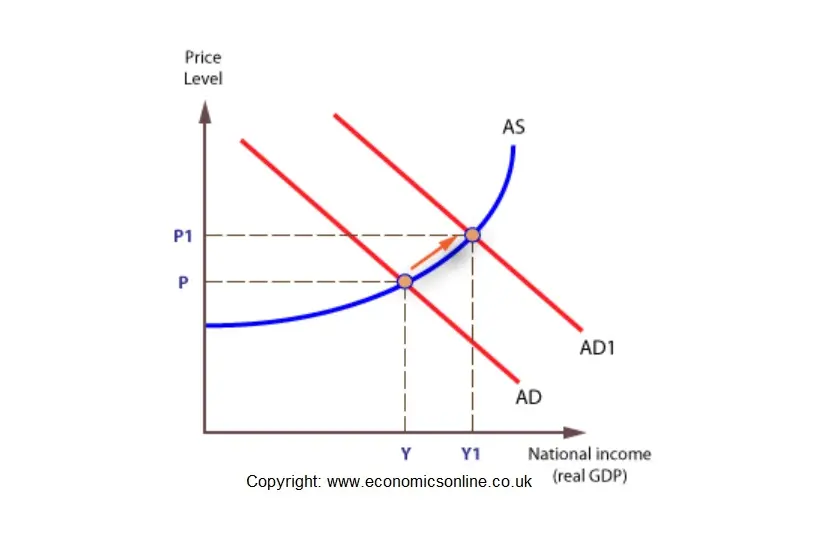

An increase in AD, such as that caused by an increase in household spending, is shown by a rightward shift in the whole AD curve.

The shift in demand will have an effect on the price level and national output, but the effects may not be uniform because aggregate supply (AS) may not be linear.

The non-linearity of AS reflects variation in the elasticity of aggregate supply.

Full employment

If the economy is already near full employment (at Yf), with only a small output gap, any increase in AD will result in price inflation, but little increase in output.

With a small output gap and an inelastic Aggregate Supply curve the inflationary effects of a sustained increase in Aggregate Demand will be considerable.

This increase in AD clearly poses an economic problem, as the economy cannot cope with the extra demand. However, Classical economists would argue that the macro-economy will self-adjust back to the full employment level.