Healthcare as a merit good

Healthcare as a merit good

Healthcare is classified as a merit good because consuming it provides benefits to others as well as to the individual consumer. For example, while inoculation against a contagious disease generates a private benefit to those inoculated as well as others. However, few would choose inoculation only to protect others. Therefore, the demand for healthcare will be less than the socially efficient quantity.

Funding healthcare

‘Comprehensive, universal and free, from cradle to grave’ was the stated aim of the NHS when it was established in 1948. However, the cost of healthcare provision has risen to such a level that many believe it is unsustainable.

The development of new technology, new treatments, and new drugs increases the NHS’s ability to supply, but at the same time encourages demand to such an extent that demand substantially exceeds supply. This creates long waiting lists and shortages of hospital beds. A privatised NHS would allow prices to rise to reflect the true cost of supply. This would, of course, violate the principle of free and universal treatment. However, rising costs have forced a re-think on funding.

he NHS is highly labour intensive, employing 1.7 million people. Indeed, only the US department of defense, the Chinese army, Wal-Mart and McDonalds employ more. (Source: BBC) This partly explains the enormous cost of funding the NHS. In 2013/14, spending by the NHS was £109.72b – approximately 20% of all government spending – £2,000 for every person in the UK.

(Source: DH website).

The cost of a night’s stay at a private hospital is around £400, excluding treatment, and a course of treatment could cost up to £300,000.

Extra public money is unlikely to be enough to keep pace with the projected increase in demand for healthcare, which is being driven by an aging populating and rising expectations. In 2005, 17% of the population was over 65 and by 2015 it will rise to 25%.

Funding options

Funding of UK healthcare was the subject of the Wanless Report, named after report chairman, Derek Wanless. The report, which was published in 2002, considered four main options for funding healthcare, in two broad categories:

Publicly funded

- Taxpayer funded, where healthcare funded by the taxpayer out of general government funds, using tax revenues from all sources, namely the current UK system. Healthcare is provided free to patients, with resource allocation being driven by need, rather than income and the operation of the price mechanism.

- Social insurance, where employees and employers make compulsory contributions towards healthcare and where provision is also free at the point of need. This is often called the European model of healthcare funding.

Privately funded

Private insurance – where individuals pay premiums (insurance fees) to private companies, and then ‘claim’ when receiving treatment. This approach dominates healthcare funding in the USA, although it is currently under review given the large numbers of American citizens who have no private insurance, or who are significantly under-insured.

‘Top-up’ private insurance means taking out insurance cover in addition to taxpayer funded or social insurance.

Out-of-pocket payments, where patients pay doctors or hospitals directly for their treatment, such as paying a fee for each visit to the doctor, for each treatment or medicine prescribed.

Wanless recommended that the current system, based on general taxation, should continue because it achieved the right balance between equity and efficiency.

The report was particularly critical of private insurance, regarding a system based on private insurance as:

- Inequitable – unfair on the less well-off.

- Having high administration costs

- No incentive for cost control – note the problem of third-party payment.

The report was also against the use of out-of-pocket payments, because they lead to inequity and regressiveness. However, it accepted that the NHS should consider charging for non-medical services like bedside TV and phones. Wanless also recommended that the government should attempt to provide greater choice for patients.

Healthcare and moral hazard

If government intervenes to increase the supply of healthcare, there is a potential government failure in the form of moral hazard.

This means that individuals, knowing that they can get free and effective healthcare, fail to take steps to avoid the risks that the healthcare insures against. For example:

- Over-eating, because people know that there is free treatment for the problems associated with obesity, such as tablets for high blood pressure.

- Smoking, because lung infections can easily be treated with antibiotics.

- Drug abuse, because emergency treatment is freely available.

The problem of third-party payment

In attempting to resolve the problem of healthcare provision and funding, private insurance has been promoted as an alternative to government funding. However, because a third-party, the insurance provider, bears the cost of any claim, there is an incentive to inflate claims and squander scarce resources.

This is referred to as the problem of third party payment, and in such cases insurance suppliers simply pass on the cost to all policyholders.

Creating internal markets

The NHS is centrally funded and has been so since its formation in 1948. However, given that governments may fail to allocate funds efficiently, and many believe that the NHS should be managed more like a private enterprise.

While most economists accept the inevitability of public funding, in order to reduce inefficiencies, many favour the use of internal markets within the existing state funded structure. These markets are often referred to as quasi markets, and they have become increasing seen as an effective means of allowing the price mechanism some role in healthcare resourcing.

As part of these reforms, hospitals may compete with each other for patients from all over the UK, creating an element of competition that previously did not exist. Patients can exercise their choices, electing to be treated in the hospital of their choice. The most popular hospitals, and presumably the most efficient ones, treat more patients and gain more income from the taxpayer. As with real markets, resources are allocated according to consumer preferences.

In addition, hospitals can contract out elements of their service, such as hospital cleaning, meals and ambulance services.

The problem of free healthcare

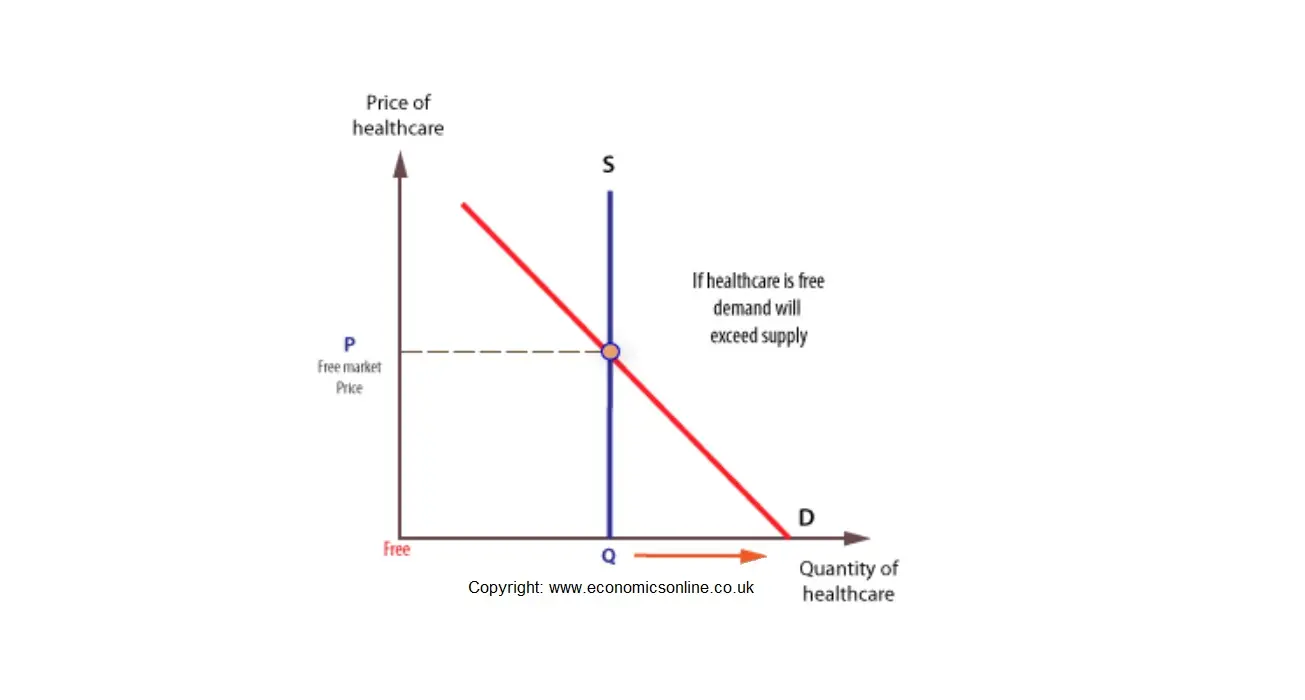

Given that hhealthcare is a merit good, it is largely provided free at the point of consumption. This means that the price mechanism cannot work to ration scarce resources, as it would for private goods. However, having no price means that there will be a shortage, given that demand will expand to its maximum. This will mean that health resources must be rationed through some other system, such as waiting lists. To understand why a shortage will arise we need to consider the supply of, and demand for, healthcare at different prices.

In the short run the supply of healthcare is fixed, and the supply curve is perfectly inelastic.

The demand for healthcare is at its greatest when it is free to patients, and this means that there is an excess of demand over supply, with waiting lists for treatment and shortages of beds. In this case, waiting lists ration healthcare treatment, rather than charges.