Merit goods

Merit goods

The market for merit goods is an example of an incomplete market. Merit goods have two basic characteristics:

Firstly, unlike a private good, the net private benefit to the consumer is not fully recognised at the time of consumption. Net private benefit is the utility from gained from consumption less any private cost incurred, and equates to net consumer surplus. In the case of education, which is widely considered to be a merit good, pupils and students cannot possibly know the specific private benefit to them of getting good grades at school, college or university. They will be well aware of the sacrifice required to study, but will not know the benefits to them in terms of a future job, salary, status and skills. Therefore, with education, as with other merit goods, there is a significant information failure in terms of expected benefits.

Secondly, consumption of a merit good also generates an external benefit to others, from which society gains, but such benefits are unlikely to be known or recognised at the point of consumption. Given that decisions to consume are driven by self-interest, it is unlikely that this external benefit will be taken into account when the consumer of a merit good evaluates its worth. For example, an individual student is generally not motivated to study hard in order to benefit others later in life, although everyone associated with them will benefit from their education in some way. Beneficiaries include future employers and all those who consume the products supplied their employer, their family, and friends. The better job they obtain, the more tax they will pay, and the greater the benefit to those who receive welfare benefits and transfers. However, putting a value on these external benefits is impossible, especially at the time of studying.

Healthcare

Healthcare is also regarded as merit good. For example, although it is not possible to know exactly when the benefit will arise, inoculation against a contagious disease clearly provides protection to the individual, and yields a private benefit. There is also an external benefit to other individuals who are protected from catching the disease from those who are inoculated! However, few would choose inoculation simply to protect others!

The supply of merit goods

Economic theory predicts that while markets may form to supply some merit goods, total supply will be insufficient to achieve a socially efficient level of consumption. A number of factors explain the lack of merit goods in a free market economy.

There is a significant level of information failure, in terms of both the private and the external benefits resulting from consumption of merit goods. For example, there is likely to be considerable information failure in terms of recognising the benefit to themselves, and to others, of regular health checks, eye tests, or visits to the dentist.

There may also be considerable time lags in deriving the benefit of a merit good. This is clearly the case with education, where the private benefits may not occur for ten or twenty years after consumption.

Given the assumption that individuals are driven by self-interest, we can also assume that the external benefit of consuming a merit good is not likely to be included in the private calculation of buyers and sellers. However, society needs as many people as possible to be educated and healthy so that all individuals can receive the maximum external benefit.

Finally, individuals and families who have low incomes are not likely to be able to pay the full market price for merit goods, and will, therefore, under-consume. For example, to continue to supply private education, tuition fees must be set to cover the full costs of supply. However, private fees are likely to be well in excess of what many low income families could afford to pay.

Because of the above, it is likely that merit goods will be under-consumed and under-supplied.

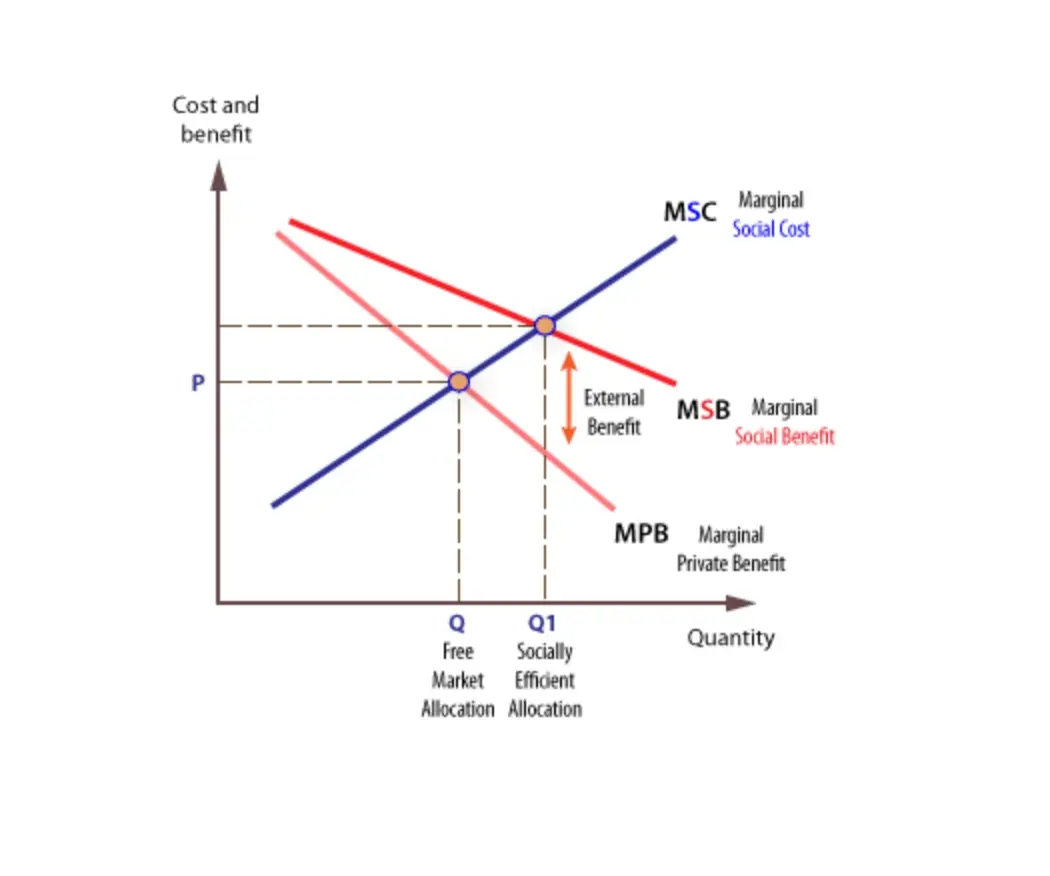

In a free market, the supply curve reflects marginal private cost (MPC), and the demand curve reflects the marginal private benefit (MPB), or utility, expected from consumption.

However, what consumers expect in terms of the marginal private benefit gained by them at the point of consumption is likely to be somewhat lower than the actual benefit. This is because individual consumers of merit goods, understandably, fail to perceive the true benefit to them – much of the benefit may arise so far in the future that it cannot possible be calculated. This information failure results in under-consumption.

Hence, on the graph, the actual marginal private benefit is higher, and to the right of the expected benefit curve.

Merit goods and positive consumption externalities

With education, few students will know with any precision the benefit to themselves of being educated, let alone the benefit to others. In other words, there is imperfect information.

Remedies for the under-supply of merit goods

Markets frequently fail to allocate sufficient resources to the production of merit goods; hence governments may need to intervene and create an environment in which markets for merit goods can form. The basic options are to adopt measures that increase consumer demand, or increase supply.

Measures to increase supply

Traditional market theory suggests that supply will increase in one of two fundamental ways; either following a rise in price, which provides an incentive for private firms to enter the market, or by a subsidy, which reduces the costs of supply.

A third way is to increase supply via some small nudges – for example, doctor’s surgeries could be required to stay open for longer each day.

While a higher price encourages supply, it also discourages demand and results in less demand for a merit good. Hence, a subsidy may be preferred as it encourages both supply and demand. Government could also choose to by-pass the market all together and take over full responsibility for supplying the socially efficient quantity of merit goods. This is what happens with State education, healthcare, and national insurance.

Alternatively, the government could pay the cost of supplying a merit good, and request that the individual consumer makes an ‘out of pocket’ contribution to these costs, such as with prescription charges for healthcare.

Government could also cover some of the costs of private sector provision, such as providing free training for doctors, nurses and teachers, who may then work in private hospitals and schools.

In addition, government could also encourage private firms to enter the market by offering incentives. For example, private hospitals could be given cash incentives to increase the number of hospital beds available to National Health Service (NHS) patients, and private schools could be given grants to take state school pupils.

A key problem when trying to increase supply is insufficient knowledge both in terms of how much to increase supply by, and in understanding the effects of intervention, and any unintended consequences.

Measures to increase demand

A second approach to merit goods is to increase demand for them. This can be achieved either through lowering price, which would expand demand, or by shifting the position of the demand curve.

What price to set for a merit good is an issue facing policy makers. One option is to provide the service free at the point of consumption, as currently exists with NHS treatment. This would expand demand to its maximum, but it may encourage over-consumption, with the system becoming clogged-up with free riders and malingerers, diverting resources from the genuinely sick and needy.

With education, a voucher system is a frequently proposed option to encourage demand for merit goods provided by the private sector. This system can be used to create a quasi market. Typical voucher schemes involve parents being allocated education vouchers, which they are then free to spend on any school of their choice. Parents can combine the vouchers with their own finance to pay for a place at any school – either state or private. Supporters of vouchers argue that they allow a market to be completed effectively and in a way that enables poorer families to have access to the best schools. Over time, this will drive up the quality of all schools as they compete with each other for scarce vouchers.

Follow link for article on educational vouchers.

Finally, demand for a merit good could be increased providing knowledge, so that the consumer can make a more informed appraisal about the benefits of consuming merit goods.

Regulation

Whenever government allocates resources on behalf of citizens, a potential principal-agent problem may arise. This means that public sector managers and employees may act in their own interests, and not in the interests of the government or taxpayer. In order to solve this problem, regulation may be necessary to ensure that the highest possible standards are achieved. For example, government may establish educational standards such as the national curriculum, and may set national targets for reducing hospital waiting lists. Regulations can help achieve standards in public healthcare and education that would occur in a more competitive environment.

See Demerit goods