Competitiveness

Competitiveness

In an increasingly market-driven global economy, a national economy needs to be competitive to develop and prosper.

Competitiveness means the ability of a country to compete effectively in global markets.

Measuring competitiveness

There is no single method of measuring competitiveness, hence it can be measured in a number of ways, including:

- Relative export prices, which are one country’s export prices in relation to other countries, expressed as an index.

- A country’s terms of trade, which is an index of the ratio of a country’s export and import prices.

- Labour productivity, which is usually expressed as GDP per worker, or GDP per hour of employment.

- Unit labour costs, which are the cost of labour per unit of output.

Types of competitiveness

Price competitiveness

Price competitiveness refers to how well UK exports compare in terms of price. This is affected by a number of factors, including:

- Relative inflation – even small annual differences can build-up over time and become significant.

- The relative real exchange rate (RER) – which is the nominal exchange rate deflated by an index of prices. In the UK it is measured by dividing the trade weighted Sterling Index by the RPI (or the Consumer Price Index – CPI), x 100. For example, if the Sterling Index rises by 7% and UK prices rise by 2%, the RER is 107/102 x 100 = 105, hence the real value of Sterling rose by 5%.

- Labour costs – including wage and non-wage costs, such as employer contributions to pensions.

Non-price competitiveness

Non-price competitiveness refers to how well UK exports of branded goods and services do in overseas markets in aspects of competition not associated with price, such as:

- Product quality and design.

- Business Research and Development (R&D), especially new product development

- Product reliability

- The strength or weakness of ‘local’ brands

- The effectiveness of marketing in overseas markets

- Levels of productive and dynamic efficiency of firms.

- Levels of ‘x’ inefficiency, including poor management, excessive bureaucracy, and government failures.

- How effective the economic and political system is in allowing markets to form – are there missing or incomplete markets?

- Investment in new technology, which helps improve quality and reliability

- Investment in human capital, which improves skill levels and reduces skill shortages – low skills, and labour shortages, can both seriously reduce competitiveness.

The World Economic Forum Global Competitiveness Report

Video courtesy of the World Economic Forum

The World Economic Forum lists the following indicators of competitiveness:

- Effective institutions – which create an economic environment in which businesses can develop, and consumers have confidence. These should be ‘sound, honest and fair’.

- Effective infrastructure – which provides effective transport and energy supplies.

- A sound macro-economic environment, including sound public finances, and low and stable inflation.

- A healthy and educated labour force, with an emphasis on higher education, and the continuous upgrading of skills.

- Efficient goods markets, with high levels of competition, and low levels of regulation.

- Efficient labour markets, which are flexible, and provide effective incentives to work and effort.

- An effective financial market, which provides a continuous flow of capital to business, effectively manages financial risk, and is trustworthy and transparent.

- The ‘readiness’ of firms to adopt new technology.

- The extent to which firms operate in large global markets, which enable them to gain from economies of scale.

- Business sophistication, which relates to the effectiveness of business networks, the quality of supporting industries, and advanced business processes.

- Continuous innovation, which counteracts diminishing returns to existing technology.

Unit labour costs

Labour costs are an extremely important determinant of competitiveness.

UK labour costs per hour have improved in recent years in comparison with other EU countries, the USA, and Japan.

Labour productivity

There are two commonly used indices of productivity:

- GDP per worker.

- GDP per hour worked.

Using either measure tells the same story – that the UK performs badly against its principal competitors.

The main causes of the UK’s poor performance are lack of investment in real capital and human capital.

The productivity gap

Whichever measure of productivity is used it is clear that the UK lags behind most of its major competitors.

The difference between the productivity of countries such as the USA, Japan and Germany, and the UK, is called the productivity gap.

In many areas of economic performance the UK out-performs Germany and other G7 countries, but not in terms of productivity.

One clear problem for the UK is the level of educational achievement. According to the Office for National Statistics (ONS) an estimated 4.5 million people have no formal qualifications, and many job vacancies cannot be filled because of a skills shortage.

Factors affecting productivity

According to research by the Economic and Social Research Council (ESRC, 2004) productivity in the UK is affected by a number of factors – many of these are included in the World Economic Forum’s index of competitiveness, especially labour market flexibility and the use of new technology.

Competition in the product market

The level of competition in product markets raises innovation and productivity for three reasons:

- Entry or the threat of entry into a market forces incumbents to become more efficient and innovate.

- Entry and exit forces firms with low productivity to leave the market.

- Incumbents may copy the more efficient and innovative new entrants.

The level of capital investment

The level of investment per capita in the UK is considerably lower than in other advanced economies. The ESRC considered a number of possible causes, including the growing skills shortage – because skilled labour is in short supply, capital machinery may be less effectively used. In addition, because wage costs are relatively low in the UK, there is less incentive for UK firms to substitute capital for labour, unlike in Germany for instance, where labour is relatively expensive.

Information technology

It is clear that the widespread use of IT in the USA has raised productivity levels there. The ESRC suggests that the use of IT in Europe lags behind that in the USA because of lower levels of competition, higher levels of regulation and less desire to change management practices to incorporate more IT.

Innovation and technology transfer

Again, the lack of competition in the UK and European product markets may help explain the lower levels of R&D as compared with the USA.

Skills and Human Capital Development

The ESRC argues that a relative lack of skills in the UK is a primary cause of the UK’s productivity gap. The lack of management skills appears particularly acute. It is argued that the best graduates go into finance, accounting, and consultancy rather than into management.

Skills shortages and skills gaps

A skills shortage is a situation where there is a shortage of individuals in the labour market with the skills necessary to meet labour market demand. A skills gap means that current employees do not have the necessary skills that employers require.

Flexible labour markets

The share of total UK employment composed of part-time work is high compared with many other advanced economies, and is above the EU and euro-area average.

In comparison, the EU has a greater % of temporary work and self employment.

All these types of employment have risen at the expense of full-time permanent employment.

Wage flexibility

Flexible wages can also create the right economic environment for economic growth.

Investment

Another significant determinant of competitiveness is investment per head.

Investment leads to:

- Improved productivity.

- Reduced inflationary pressure, hence improved price competitiveness – by shifting aggregate supply to the right.

- Improved quality, design and reliability of products.

The UK’s investment record

Investment is a key determinant of economic growth, productivity and competitiveness.

The level of investment is determined by:

- The level of undistributed profits, which are profits retained by firms rather than distributed to shareholders.

- The level of savings, which provides a flow of funds for investment and helps depress interest rates.

- Interest rates – investment is inversely related to interest rates.

- The level of business tax – lower business taxes may be an incentive to invest if firms are given tax allowances for the investment the investment they undertake.

- Business confidence – investment is a sacrifice and firm’s expectations of profits have a powerful influence on investment decisions.

- Changes in national income, via the accelerator effect.

- In addition, factors affecting FDI, such as human capital accumulation and investment incentives.

Investment and interest rates

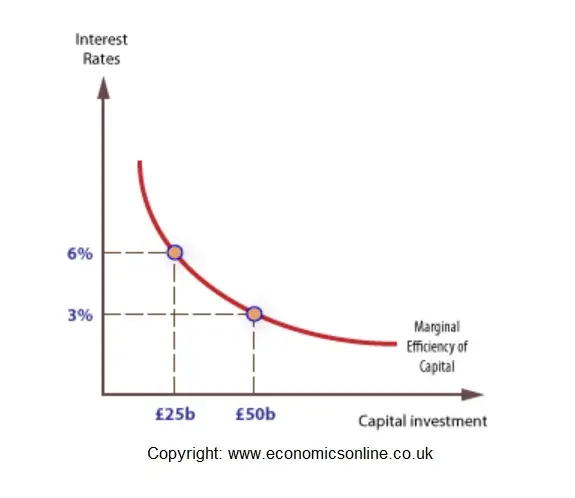

Marginal efficiency of capital

The demand for investment is negatively related to interest rates. For example, at a rate of interest of 6%, the level of investment is £25b. At a lower interest rate, such as 4%, the profitability (efficiency) of capital is higher, and demand for capital is greater, at £50b.

Conversely, lower interest rates stimulate investment. Hence, the demand curve for investment slopes down from left to right.

UK’s investment in manufacturing

The poor level of UK investment in manufacturing over the last 20 years can be attributed to:

A relatively low savings ratio

Low savings and high consumer borrowing and debt levels reduce the supply of funds for investment in manufacturing as well as raise long term interest rates.

Relatively high interest rates

As illustrated by the MEC diagram, demand for investment falls when rates are high because of the higher opportunity cost of investing. Typically, over the long term, UK rates have been marginally higher than those of the UK’s main competitors, including the USA, Japan and the euro-area (EA-19).

More attractive investment alternatives

Alternatives to manufacturing investment in the UK may be particularly attractive, including foreign direct investment, shares, property, and the service sector.