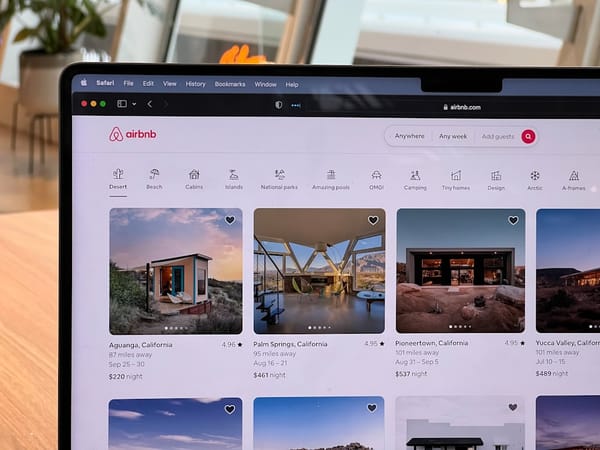

Photo by Andreas Klassen / Unsplash

The Productivity Paradox of Remote Work

When the Covid pandemic hit in early 2020, millions of white collar workers were thrust into remote work. Instead of commuting to their offices and cubicles every day, these workers simply logged into their work portals through their personal computers at home. Many white collar employees quickly voiced support for working remotely. However, in the five years since the pandemic, companies’ support for remote work has diminished. The past few years have seen return to office mandates passed by many large companies, sparking debates over the purposes of these mandates and which side is correct about worker productivity.

The Productivity Argument

Both sides of the remote work debate have argued that productivity is affected, though their respective rationales are different.

Pro-Remote Work

Supporters of remote work argue that productivity is increased due to more time on task and greater worker satisfaction. More time on task is achieved through remote work by removing work tasks or expectations that are not directly linked to creating output, such as “water cooler chitchat” or commuting. Remote workers argue that they are able to be “in the zone” when working from home because they are not having to deal with regular social interactions with colleagues.

Greater worker satisfaction from being able to work from home is argued to improve productivity through improved worker health, both mental and physical. Essentially, happy workers are more productive workers and, because they feel grateful to their employer for allowing better work-life balance, will work harder for their generous employer. Proponents of remote work argue that, across large companies, remote work policies increase productivity and reduce costs by improving worker retention and reducing the need to recruit and train many new employees. Happy workers are loyal workers, and thus stick with the company and reward it with the benefits of their experience and improved skills.

Anti-Remote Work

Critics of remote work argue that productivity is decreased due to lack of oversight and the stimulation of in-person collaboration with colleagues. Some studies reveal that remote workers overstate their productivity and, in fact, spend some work hours engaging in recreation. Despite many companies’ efforts to use workflow monitoring software, such as tracking the amount of time remote workers are logged in to company websites, some workers have come up with ways to fool these productivity trackers. For example, some monitoring programs notify supervisors when a remote worker’s mouse cursor has not moved for a while…so workers use various means to move their mouse in their absence, making it appear that they are at their computer.

Even if remote workers are laboring diligently at home, some critics of remote work contend that they are still underperforming by assisting less with company innovations and spontaneous problem-solving than in-office workers. Breakthroughs allegedly occur less frequently when team members work remotely, resulting in less productivity growth. These critics argue that it is almost impossible to replicate the energy of in-person collaboration, especially when it is spontaneous, across digital communication tools like Zoom, Google Meets, or Slack. Nothing, they argue, beats in-person collaboration.

Productivity Paradox: Remote Worker Efficiency May Wane in Long Run

Many employers have maintained remote work for now due to strong pressure from workers, who argue that their improved work-life balance makes them more productive. However, studies show no long term gains in productivity from remote work. This “plateau” in productivity for remote workers may be due to the lack of in-person and spontaneous collaboration, reducing innovation.

Even the initial productivity benefits of improved work-life balance may erode in the long run, as many remote workers allow boundaries between work time and personal time to become eroded. Workers may become complacent about ensuring their focus on work during on-the-clock hours, allowing declines in productivity to slowly accumulate. For example, an experienced remote worker may underestimate the amount of personal time he or she is “borrowing” from work hours and overestimate the amount of off-the-clock hours “repaid” to compensate. Thus, by the end of a week, a remote worker may inadvertently be shorting the company several productive hours.

Possible Solutions to Productivity Struggle

Hybrid Schedule

Many white collar companies that went mostly remote during the Covid pandemic have not returned entirely to in-office work for the entire work week. Instead, they have adopted hybrid schedules that allow employees to work remotely for some of the week and be in the office only part-time. For example, these white collar workers may come to the office on Tuesday and Thursday to collaborate with their respective teams but work from home on Mondays, Wednesdays, and Fridays. This has been praised by some as allowing for the “best of both worlds” - maintaining better work-life balance for employees while ensuring enough time for the innovation and team-building of in-person work.

Measure Outputs Instead of Hours Worked

The debate over whether remote workers are providing their employers with sufficient labor-hours often becomes overwhelming and full of nit-picking. To avoid spending tremendous resources on tracking remote worker compliance, such as monitoring their activities on company websites, employers can simply track only the finished product. If the remote workers’ outputs meet standard, why worry whether it took them 40 hours per week or 30? After all, should a more efficient worker be penalized for completing a task to a satisfactory degree in less time than a colleague?

Determine Which Workers Truly Need to be In-Person

Not all white collar workers may necessarily need to be seeking innovations or team-building. Companies may be able to enjoy sufficient innovation by deliberately keeping innovators in the office while allowing non-innovators to work from home. While this process will undoubtedly be controversial, with many employees in innovator roles desiring to continue working from home, it will pay dividends if done with fidelity. Innovators may be given a choice, such as allowing them to transition to a non-innovator role, if they do not relish the prospect of returning to the office.

Ultimately, many large companies are likely to adopt some degree of all three strategies to maximize the benefits of both remote work and in-office innovation. Innovators may be required to be in the office 2-3 days per week, while non-innovators can continue to work from home. These remote workers will be evaluated solely by quality output generated, with little formal oversight of their hours worked.