Growth of firms

Growth of firms

The long run for a single firm is entered when it uses more fixed and variable factors to increase its scale of production.

The long run average cost curve (LRAC)

A typical long run cost curve is ‘U’ shaped because of the impact of economies and diseconomies of scale.

Growth

Firms grow in order to achieve their objectives, including increasing sales, maximising profits or increasing market share. Firms grow in two ways; by internal expansion and through integration.

Internal expansion

To grow organically, a firm will need to retain sufficient profits to enable it to purchase new assets, including new technology. Over time, the total value of a firm’s assets will rise, which provides collateral to enable it to borrow to fund further expansion.

The importance of branding

One of the most common strategies for internal growth is to build the firm’s brand, which provides the firm with many advantages. Once a brand is established, less advertising is required to launch new products. Internal growth often provides a low risk alternative to integration, although the results are often slow to arrive.

External expansion

The second route to achieve growth is to integrate with other firms. Firms integrate through mergers, where there is a mutual agreement, or through acquisitions, where one firm purchases shares in another firm, with or without agreement. There are several types of integration, including:

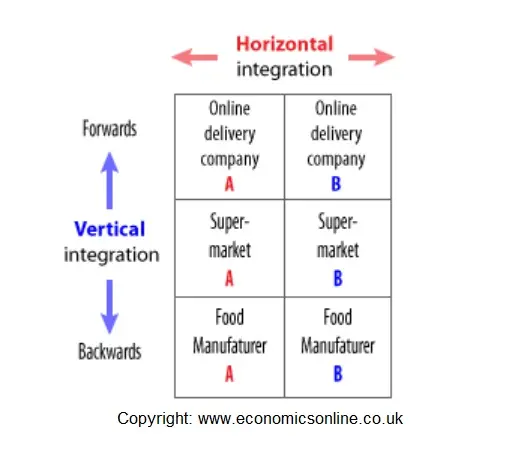

Vertical integration

Vertical integration occurs when firms merge at different stages of production. There are two types of vertical integration, backwards and forwards.

Backwards

Backward vertical integration occurs when a firm merges with another firm which is nearer to the source of the product, such as a car producer buying a steel manufacturer.

Forwards

Forwards vertical integration occurs when a firm merges to move nearer to the consumer, such as a car producer buying a chain of car showrooms.

Horizontal integration

Horizontal integration occurs when firms merge at the same stage of production, such as a merger between two car producers, or two car showrooms. Horizonal integration is also referred to as lateral integration.

Conglomerate integration

Conglomerate, or diversified, integration, occurs when firms operating in completely different markets, merge – such as a car producer merging with a travel agency. In this case, firms tend to retain their original names, and are owned by a ‘holding’ company.

Test your knowledge with a quiz

Press Next to launch the quiz

You are allowed two attempts – feedback is provided after

each question is attempted.

Multi-nationals

Many firms grow by integrating with foreign firms, which is increasingly common in the globalised world economy, and is a key part of the globalisation process. Cross-border mergers contribute to inward investment between countries. The UK is a major global investor, and in 2013 was second in the world league table for receiving FDI (Foreign Direct Investment), with inward investment of $1.6tr. (Source: UNCTAD, 2013). Mergers and acquisitions account for a large share of FDI.

Bank mergers

Like all firms, banks can derive considerable benefits from merging, including economies of scale. In addition, there are considerable benefits to financial institutions from merging rather than expanding organically. Over time, banks will have built up a range of low, medium, and high-risk borrowers. To expand organically, a bank may have to take on higher risk customers. However, if a bank acquires another bank it will not need to increase its average risk because it will acquire a range of customers of all risks. Banks can also merge to help secure extra liquidity.

The advantages of mergers

Mergers can generate a number of advantages:

- Firms that merge can take advantage of a range of economies of scale, such as cost savings associated with marketing and technology.

- In the case of vertical integration there are savings in terms of not having to pay ‘3rd party’ profits. For example, if a tour operator owns its own hotels it will not need to pay profits to the hotel, and will be able to keeps costs and prices down.

- Economies of scope are also available to firms that merger and are benefits associated with using the fixed assets of one firm to produce output for the other firm.

- Unexpected synergies are unpredicted benefits that arise when firms merge or undertake a joint venture, such as when two pharmaceutical companies merge, and create a new drug.

- Rationalisation is the process of eliminating parts of a business that are inefficient or unprofitable, and is a possible consequence of two or more firms merging.

- When firms merge, they can share knowledge with each firm benefitting from the knowledge and experience acquired by the other. With vertical integration, information asymmetries can be reduced or removed.

- The merger of two firms may send out a signal to other firms not to attempt a take-over bid.

- Firms that merge may be able to allocate more funds to Research and Development (R&D) and generate new products as a consequence. This may increase their competitiveness and profitability in the long run.

Disadvantages of mergers

- Increased concentration and reduced competition are obvious disadvantages of a merger between two dominant firms.

- Firms that merge may experience diseconomies of scale, such as difficulties with co-ordination and control. This will increase average cost in the long run, and reduce profitability.

- Higher prices are a likely consequence of a merger because, with less competition, demand is more inelastic and raising price will raise revenue.

- There may be less output from the merged firm, compared with combined output of the two firms.

- Rationalisation is likely to lead to lost jobs as the merged firms attempt to increase profitability. For example, two advertising agencies that merge could dispense with two design departments, and share one.

- Consumers are likely to suffer from reduced choice following a merger of two close competitors. This is a common criticism of banking and supermarket mergers, and one reason why they are the subject of scrutiny

- The economies of scale and scope derived from a merger may increase barriers to entry and make the market less contestable. In the case of forward vertical integration, new entrants may be denied access to outlets for its products. With backwards vertical integration, new entrants may find it difficult to secure a source of supply of materials or products.

- Merged firms may have more monopsony power which they may use to dictate terms of business to suppliers, or keep wages below the competitive market equilibrium.

Policy towards mergers

In the UK mergers are assessed in terms of the specific circumstances of each case.

Substantial Lessening of Competition (SLC)

There are several considerations when making an assessment of a merger – the most important of which is whether there will be a substantial lessening of competition (SLC). This refers to the potential loss of competition which may result from a merger.

There are considered to be three main categories where a merger can lead to a lessening of competition:

Unilateral effects

Unilateral effects arise when a single combined firm is able to raise prices in a profitable way given the lessening of competition that follows the removal of a rival. The closeness of the firms as substitutes for each other will clearly have a bearing on the assessment of unilateral effects.

Co-ordinated effects

Co-ordinated effects occur when several firms are more likely to jointly increase their price. For example, firms may carve-up a market in a geographical way, and with less competition raise their price. In this instance production may be limited or innovation stifled. Tacit collusion is example of a co-ordinated effect.

Vertical effects

Finally, vertical effects are associated with vertical integration and may arise when a merger strengthens the ability of the merged firm to exert its power in the market.

The counterfactual situation

In deciding whether a merger will lead to a substantial lessening of competition the OFT or CC will consider the likely foreseeable competitive situation that would have arisen if the merger had not gone ahead – called the counterfactual. For example, it may be likely that a new firm would have entered the market were it not for the merger. It is also possible that one of the merged firms may have left the market had the merger not gone ahead. The authorities (the OFT and CC) may also consider, as part of the counterfactual analysis, whether a different bidder would have come forward.