The Sharing Economy’s Hidden Costs: From Access to Precarity

If everyone can do something, how valuable is it? The rise of the gig economy in recent years, thanks to the ability of smartphone apps to allow workers, employers, and customers to connect in real time, has resulted in declining wages. On the surface, the gig economy was advertised to prospective workers as a way to share the wealth of strong consumer demand - anyone could perform the quick tasks needed to make income. Unfortunately, the once-great promise of the gig economy has turned out to entail significant costs for unwary workers.

Sharing Economy Defined

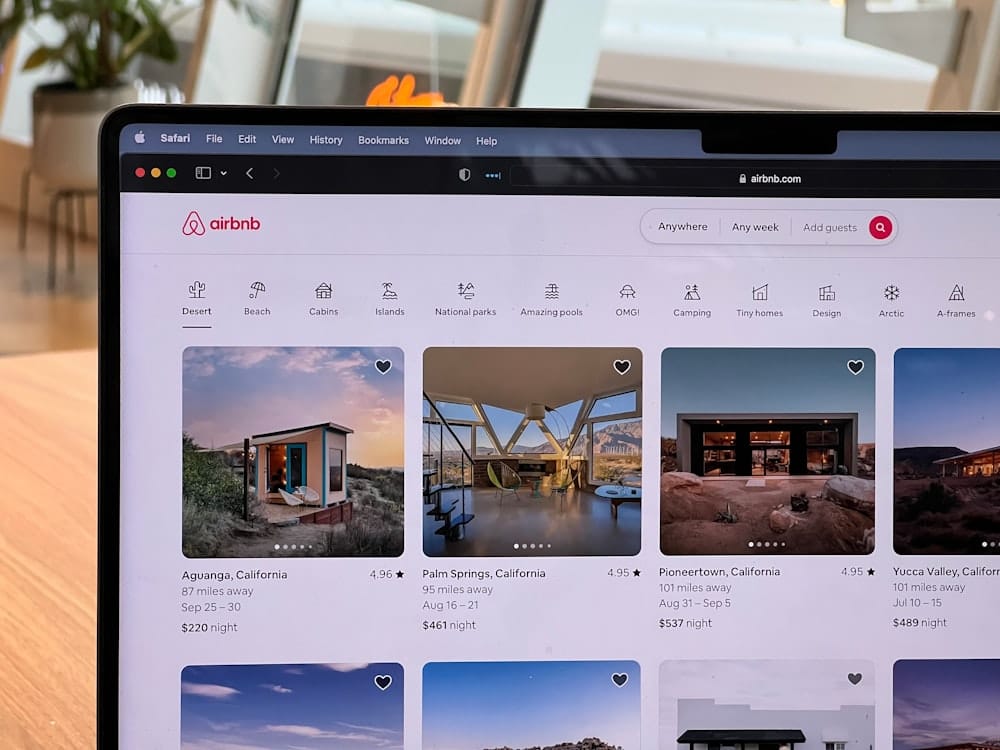

The term “sharing economy” refers to “shares” of underutilized (not used fully) assets like cars and houses. Entrepreneurs realized that these assets could be used to make revenue during the time when they were not being used by the owner. Houses and apartments, for example, could be rented out on a short-term basis when unused, bringing in revenue from tourists and business travelers. This created the huge markets for Airbnb and Vrbo, which allowed homeowners to rent out unused properties and generate quick revenue for virtually no marginal cost.

Rideshare apps like Uber and Lyft combine the gig economy and the sharing economy, with owners using their own labor to take advantage of their underutilized automobile assets. During their free time, they can “clock in” on the app and accept fares to give customers rides. In many ways, most jobs in the gig economy are also part of the sharing economy because workers are using their own assets, ranging from smartphones to houses, to sell services. Freelance writers and artists, for example, use their own computers and software to generate finished products for paying customers.

Economics of the Sharing Economy

Low Marginal Costs

The sharing economy is largely based on very low marginal costs, meaning the worker or seller spends almost no money to make revenue from his or her assets. For short-term property rentals, the marginal costs may be near zero - insurance, taxes, and landscaping fees are already paid. A customer may rent the house for a weekend for $200 but only use $20 worth of utilities like electricity, water, and natural gas, meaning a high profit margin for the homeowner. Many property owners on short-term rental apps also include restrictions on use of their property that could incur higher marginal costs, such as cleaning expenses. If renters violate these restrictions and cleaning costs are necessary, these can be charged to the renters.

Rideshare apps incur more marginal costs, as vehicles use fuel for each trip, but the revenue almost always outweighs the cost. Some drivers may tolerate the lower profit margins because they get utility (satisfaction) from driving around and seeing different parts of the city. They may also be driving a vehicle that they would ordinarily have just let sit unused, thus making depreciation a non-concern. If drivers wish, they may even be able to rent or lease a vehicle through the rideshare app itself, thus not incurring costs on their personal vehicle.

Low Coordination Costs

The gig economy and sharing economy are convenient - buyers and sellers operate whenever and however often they want. Owners of rentable assets no longer have to place ads in a myriad of places across different mediums…they just get on the apps. If they have negative experiences, they can remove their profiles from the apps. For the most part, sellers can decide whether to accept jobs, meaning they can turn down offers when the timing or pay does not suit them.

Assumption of Risk

Workers in the gig/sharing economy get to enjoy low marginal costs and low coordination costs, but have to deal with the trade-off of low security. Risk of loss is high due to lack of job protections. For the most part, workers in the gig/sharing economy are classified as independent contractors, meaning they are ineligible for most employee benefits like health insurance, retirement plans, tax filing, or job security. Workers earn cash but have to make their own arrangements for health care, retirement savings, and filing their taxes.

Controversially, being an independent contractor also means that the company (such as Uber or Lyft) will not support workers if there is an accident. While formal employees of companies are typically covered by the company’s insurance policies, independent contractors are not. If a rideshare driver or short-term rental property owner is sued, they are usually responsible for all of their own legal fees.

The lack of formal employee status can subject some gig workers to mistreatment, either through employer negligence or intentional mistreatment. This can include wage-skimming or threatening to ban workers from the apps if they do not accept undesirable jobs. Some individual workers have sued their gig employers for allegedly taking advantage of them, perhaps thinking that they could do so because the workers lacked the resources to seek legal recourse.

Welfare Trade-Off for the Macro Economy

Consumer Surplus

Consumers benefit from the gig/sharing economy due to low prices and quick output. The technology that allows most adults to perform gig work has drastically increased the supply of low-skill labor, bringing down the cost. In a large city, finding a ride is now easier than ever. With an app available for almost every service, consumers can enjoy the cost-lowering effects of competition. However, the quality of these services may not be guaranteed. While low ratings can get a worker banned from an app, the dissatisfied rider, renter, or customer often has little recourse due to the worker being an independent contractor.

Social Insurance Erosion

Cheap services are great for consumers but bad for tax revenue. Because most income taxes are progressive, having a larger percentage of low-income workers in an economy tremendously reduces tax revenue. Gig workers are often low-paid, meaning they contribute little to social programs that are funded through tax revenue. This is compounded by the fact that gig workers must file their own taxes, and some do not do so in a timely fashion. Thus, as more workers become part of the gig/sharing economy, tax revenue declines and puts social insurance programs at risk. This increases risk of turmoil in the macro economy, as social insurance will not be readily available during recessions.