The Principal-Agent Problem

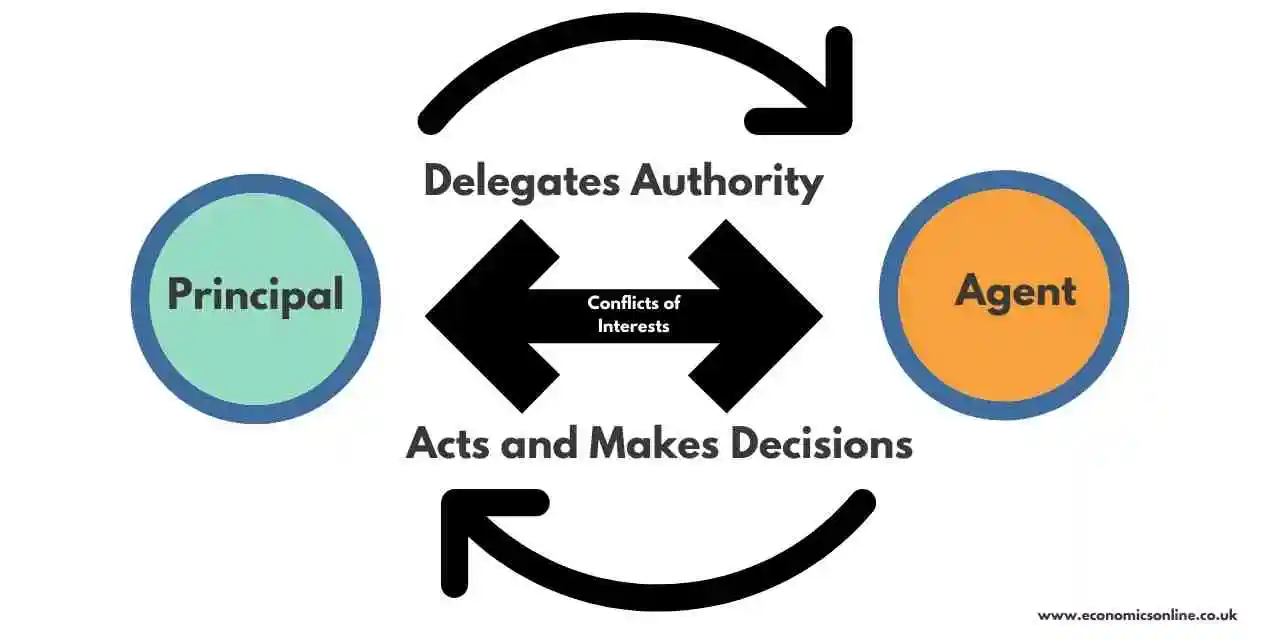

The Principal-Agent problem arises when decisions are made by an economic actor (the agent), on behalf of an overarching stakeholder (the principal). The problem occurs as agents and principals do not always have the same objectives, and are not subject to the same risks. This can cause moral hazard and lead to inefficient outcomes. As a concept, the principal-agent problem was developed by Michael Jensen and William Meckling in the 1970s.

Examples of the Principal-Agent Problem

Below we cover some frequently observed examples of the principal-agent problem:

1. Owners (Principal) vs. CEO (Agent)

2. Owners (Principal) vs. Employees (Agent)

3. Government (Principal) vs. Major Institutions (Agent)

Owners vs. CEO

The classic example of the Principal-Agent problem is the relationship between an owner of a company, in this case the principal, and a CEO or manager that they hire to run the company – our agent in this example. Typically, we think of owners as wanting to maximise the profits of the company, giving them the largest financial return. On the other hand, a hired CEO might have different interests such as achieving the highest salary possible or being responsible for large revenue growth. This is an instance of asymmetric information, as the agent generally has more information than the principal, which does not always know how the agent will act. As the principal cannot control the agent fully, the outcome may be different than their objective. This is known as an ‘agency cost’ – the cost to the principal of not getting their own way due to their reliance on the agent.

Owners vs. Employees

Airline employees working at the departure gate (our agent) often illustrate the principal-agent problem as their goals do not necessarily align with the owner of the airline (the principal). The owner wants to maximise profits, which they can achieve by filling airplanes with as many passengers as possible, ideally whilst cutting down on fuel costs. The employee on the departure gate wants to have a pleasant flight that runs smoothly, with no issues from any of the passengers. If one passenger has a very large bag that is over the weight limit, the airplane will be slightly heavier and use more fuel – the airline will be less profitable! The principal would want the employee to always charge this passenger extra, but in our example the agent would prefer to allow the passenger on to the plane with no difficulties.

Governments vs Major Institutions

Leading up to the 2008 financial crisis, executives (agents) in control of major institutions allowed their companies to utilise risky financial instruments as it aligned well with their personal incentives. When these effected serious harm to their firms, they had to be bailed out by the government – the principal. Why is the government the principal in this example and not the shareholders of the banks? In this case, the government needs bankers to build a responsible financial system to allocate money to firms, as well as to the government themselves. They are not able to do this themselves, so need banks to build the financial system that we have today. Before the crisis, bankers were able to make huge profits for their firms and receive large bonuses as a result. They knew that their banks were a necessity for the modern economy, so the government would not let them collapse - an example of moral hazard.

Solutions

Some of the most common solutions to the principal-agent problem are:

1. Stock Options

2. Profit-Sharing Plans

3. Directly Linking Management Pay to Stock Price

4. Government Regulation

Stock Options

The most effective way to solve the principal-agent problem is to align incentives between the agent and the principal. In many instances, the principal is the owner of a company. In this case, incentives can be aligned by giving the agent some ownership in the company too. This is why lots of employees receive stock options as part of their salary or bonus. If they act to limit profitability, the company’s stock price may fall, or it may pay out less in dividends, thus reducing the income of the agents.

Profit Sharing Plans

In lieu of granting actual ownership of the company to the agent, the principal may use a contract clause to guarantee a certain percentage of the company's profits to the agent, in order to better align the agent's incentives with the company's interests.

Directly Linking Management Pay to Stock Price

Another example of a contract clause, management pay could be setup to be directly influenced by their company's stock price to align the agent's interests with the principal's.

Government Regulation

In cases where governments are the principal, regulations can be used to ensure that the government's interests are represented in the actions of major institutions, which are their de-facto agents. For example, since the financial crisis, major banks are now required to hold larger capital reserves, and regularly conduct ‘stress tests’ to ensure they would not collapse even in difficult market conditions. This type of solution is of course an order complexity higher than contractual clauses. If governments execute their regulations incorrectly, they risk an onset of government failure, wherein macroeconomic challenges are not solved and present significant systemic and social risk.